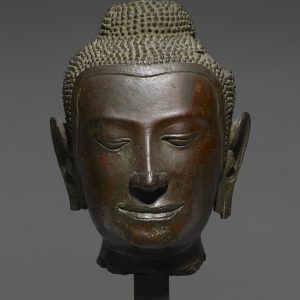

Mahācīna-Tārā

Bronze

Nepal

15th century

H. 15 cm

Description

This goddess in a frightening form has four arms holding various attributes, common to fierce deities: the cleaver (kartrikā) and the skull cup (kapāla) in the main hands; the sword (khaḍga) and an object difficult to identify in the second pair of hands. By comparison, one could assume that it is a bleeding heart, torn off with shreds of arteries and veins from the chest of an unholy man. The deity stands on a triangular sacrificial area where a corpse lies, all on a blooming lotus flower.

The goddess is named Mahācīna-Tārā and testifies to the syncretic Buddhist and Hindu tantric cults in Newar country. She is also known as Prajṅādevī. She is part of the group of 21 Tārā but is also assimilated to Prajṅāpāramitā. The legend that deals with the origin of her cult includes both Buddhist and Hindu elements. The wise Vasistha could not visualize the goddess Tārā and asked for the advice of his spiritual master, the god Brahmā. However, the goddess eventually appeared to him and ordered him to go to Mahācīna in order to meet Buddha, the ultimate avatara of Viṣṇu. Thus, at the place called Mahācīna, he was able to pay tribute to Tārā, which appeared to him under this specific iconography (Mahācīna Tārā). She is sometimes confused with the dreaded Ekajatī.

Representations of this goddess are rare. The piece commented here is almost identical to a statuette once exhibited at the Marco Polo Gallery in Paris and reproduced by Ulrich von Schroeder (1981, p.366-367, n°99E). In addition to many details, the bases of the two deities are very similar, supported in the corners by square feet decorated with lions. The four doors of the yantra are treated as “hors d’oeuvres” i.e. as projecting structures. Below each of them, a carpet is scrolled and richly crafted.

Ulrich von Schroeder dates the statue to the 15th century, a period that saw the division of the Kāthmāndu valley in 1479, the beginning of the recent Malla period. Artistically, this century saw the extension of the great art of the ancient Malla (1200-1479) but often with a more decorative rendering and a tendency towards extreme iconographic diversification that would triumph in the 16th century. On the piece that we are discussing, we must mention the finesse of certain details such as the head of the feline skin tied around the waist of the goddess

Biblioagraphy: Schroeder, Ulrich von, Indo-Tibetan bronzes. Hong Kong: Visual Dharma Publications, 1981.