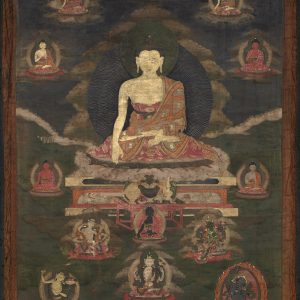

Hayagrīva

88 000,00€

Gilded bronze

Northern China

C. 17th century

H. 22 cm or 8 ¾ in

Description

In Hinduism, Hayagriva, “The Horse-headed One”, is a term designating two characters linked to the Vishnu tradition. Hayagriva is the name of a demon slain by Vishnu during the mythical Taraka battle. According to relatively recent speculation, he was reincarnated as Kesin, the youngest brother of Kamsa, thereby becoming a majestic part of the Krishna legend.

Vishnu himself, in a form with a horse’s head, promulgates the Vedas. In this frightening form, sometimes considered as one of his avatars, he exterminates certain demons such as Madhu and Kaitabha.

The exact link between the Hindu Hayagriva and the divinity of the same name in Tantric Buddhism is not known. In Mahayana Buddhism, the horse Balaha, the salvatory aspect of the bodhisattva Avalokiteshvara, is the object of a pious legend. Developments specific to Buddhism arising from this particular animal emanation might explain the relationship between Hayagriva and Avalokiteshvara. In Japan, Shingon tradition would seem to corroborate this hypothesis. Hayagriva (Bato Kannon in Japan) is considered as one of the six main avatars of Avalokiteshvara (Kannon).

The Hayagriva cycle was first preached in Tibet in the 11th century by Atisa (circa 982-1054)

Hayagriva, a minor deity, became the focus of most of the horse-based cults that Buddhism encountered during its eastward expansion. In Tibet, this god was venerated by horse merchants, apparently due to his iconography alone and not because of the rare legends that were attached to him. His cult is especially widespread in Mongolia, the horse culture par excellence.

In Tibet, this paradoxical god is now studied only rarely. However, hs is present in three specific contexts. His horse-headed aspect links him to the wind-horse Rlung-rta reproduced on many prayer flags. These wood-cuts printed on fabric are hung on masts, to float in the wind and thereby sanctify an area. This marvelous horse, bearing jewels, intercedes between the earthly world and the world of the gods. Hence he helps transmit the prayers of believers and makes magical incantations more effective. The links between Hayagriva and Rlung-rta do seem to have arisen later on, the fruit of popular beliefs born out of pious confusion. Rlung-rta probably originated in the white horse of Indra, the king of the gods, named Uchaishravas, one of the seven treasures of the Universal Sovereign.

In certain texts such as the Padma thang-yig, one of the classics of rNying-ma-pa literature telling the legendary story of the holy Padmasambhava (8th century), Hayagriva wins out over the terrible Rudra, the demonic version of the Hindu Shiva. In other traditions, this role falls to the bodhisattva Vajrapani. That explains the evocation of Hayagriva in certain exorcism rituals. His neighing is said to scare off demons. Thus many ritual daggers (Phur-bu) are adorned with one or more heads of Hayagriva (Huntinton, 1975, p. 24-25, fig. 29-31).

Hayagriva has many aspects. A horse head on the top of the skull makes it possible to identify him without question, regardless of the number of heads or arms.

In one of his works, the fourth Panchen Lama, bLo-bzang bstan-pa’i nyi-ma (1780-1852), names this avatar with three faces and six arms Khro-bo rgyal-po rta-mgrin, “Hayagrīva, the lord of the krodha”. The statuette here presents a few variations on this canonic aspect. For instance, it has only one horse head above the skull’s diadem instead of the three prescribed by the Panchen Lama. The first hand on the right holds a sword whose pommel is still perfectly visible and the third holds the “diamond-thunderbolt” (vajra). The lower hand on the left, perfectly visible, holds a cord made of human intestines and the third is making the gesture of vigilance (tarjani mudra). The attributes of the second hands, both right and left, respectively holding the trident and the arrow, are replaced here by a cord (pasha). With his eight feet, the god is trampling nests of serpents.

By their expressive and inventive nature, angry representations of deities constitute the most original aspect of Tibetan art. The menacing vision here contrasts with especially refined decoration, which is assumed to be characteristic of northern Chinese workshops under the reigns of the first two Qing emperors, expecially Kangxi (reigned 1661-1722), a period of renewed and active patronage. This work fits into the same aesthetic context as a Savara in the Asian Museum of San Francisco (Rhie-Thurman, 1991, p. 278-279, n° 102) and to a lesser extent a Buddha in the Hermitage in Saint-Petersbug (Rhie-Thurman, op. cit., p. 84-85, n° 5).

Provenance: Private collection, Bordeaux, France.

Art Loss Register Certificate, ref. S00106956.

- Rhie Marylin M. – Thurman Robert A.F., Widom and Compassion ; The Sacred Art of Tibet. San Francisco, Asian Art Museum – New York, Tibet House-Harry N. Abrams, 1991.